RESEARCH

Physical Drivers of Environmental Change

“It is a curious situation that the sea, from which life first arose, should now be threatened by the activities of one form of that life. But the sea, though changed in a sinister way, will continue to exist. The threat is rather to life itself.”

Biogeochemistry &

Paleogenomics

Ph.D. Research (2024-Present)

Advisor: Dr. Aradhna Tripati

My current research investigates how marine ecosystems record and respond to environmental change across timescales. Building on established sediment-core and carbonate-proxy approaches in paleoclimate research, I use foraminifera preserved in marine sediments to reconstruct past ocean conditions through clumped isotope geochemistry. This approach enables long-term reconstruction of variability in ocean temperature and carbonate chemistry to track how climate variability has changed the global ocean across timescales from decades to millennia. Alongside this research, I examine how coral biomineralization and symbiotic community structure respond to long-term climate variability and anthropogenic land-use change. My research integrates sub-annual coral geochemistry (Sr/Ca, δ¹⁸O, δ¹¹B, Ba/Ca, Δ¹⁴C) with ancient DNA (coraDNA) metabarcoding of coral symbionts to reconstruct the impacts of ocean warming and acidification on coral reef ecosystems. This research project is one of the first paleoclimate reconstructions to directly link centennial-scale shifts in ocean conditions to changes in Symbiodiniaceae community composition.

Quantitative Ecology

M.S. Research (2021-2024)

Advisor: Dr. Nyssa Silbiger

Intertidal ecosystems are model systems for understanding environmental change because the organisms that inhabit them experience repeated swings in temperature and seawater chemistry that often exceed future climate projections. My previous research examined how ocean warming and acidification interact to influence the physiological energetics of Tegula funebralis, a common intertidal sea snail. Along the Pacific West Coast, Black turban snails are highly abundant and play a key ecological role as a macroalgal grazer; facilitating energy transfer from primary producers to higher trophic levels — a foundational interaction that structures energy flow throughout marine food webs. In dynamic intertidal zones, T. funebralis experiences substantial seasonal and diurnal temperature fluctuations that directly influence metabolic rates (e.g, increased temperatures, increase rates of grazing activity). As oceans continue to warm and acidify due to climate change, understanding how these co-occurring stressors affect the metabolic performance of herbivores is essential for predicting broader ecosystem responses.

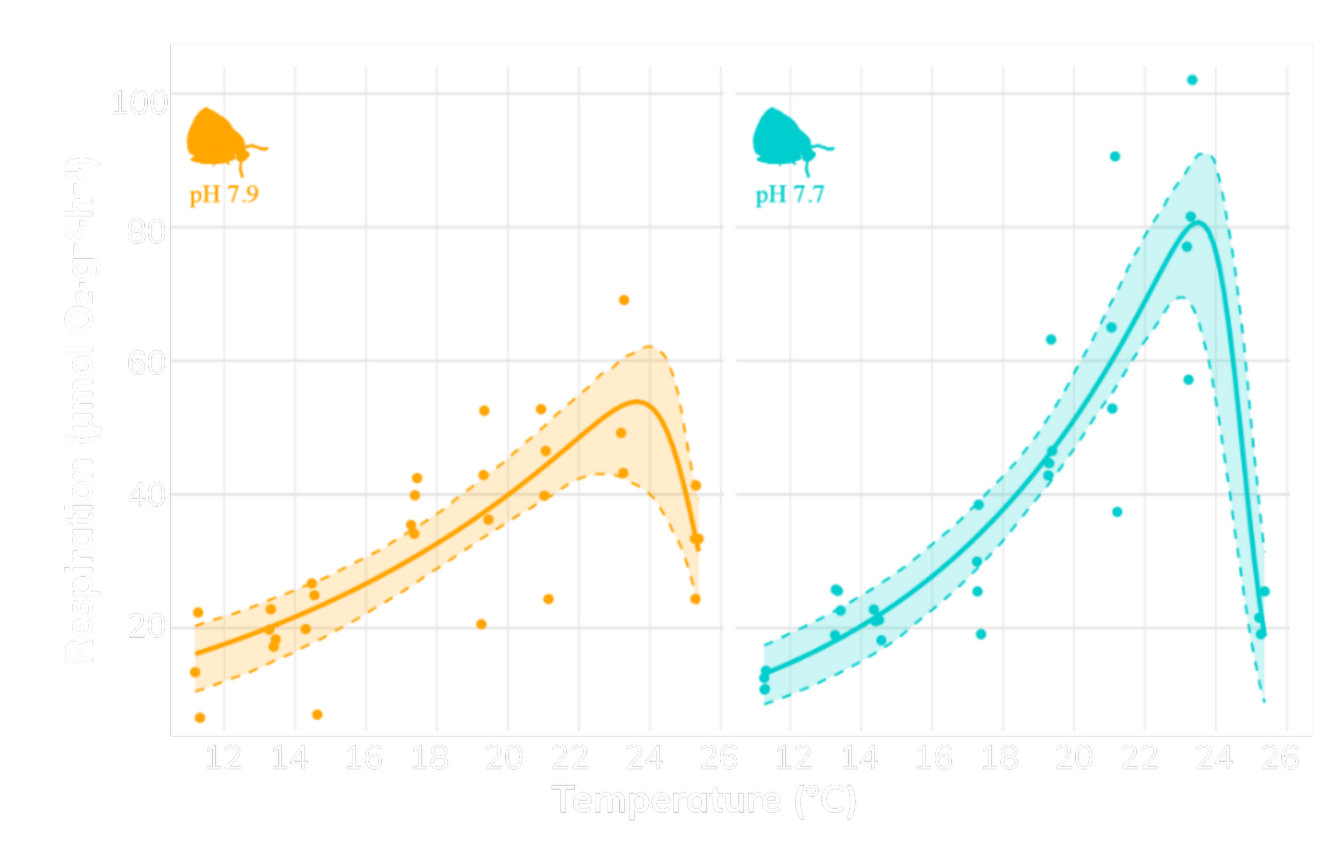

Figure: Comparative thermal performance curves of Tegula funebralis respiration rates (µmol O₂·g⁻¹·h⁻¹) across eight ecologically relevant temperatures (12°C–26°C) and between two seawater pH treatments: ambient conditions (~7.9) and reduced pH (~7.7) simulating ocean acidification. Each point reflects the respiration rate of an individual snail (ambient: n=29; low: n=31), and shaded regions represent bootstrapped 95% confidence intervals around each fitted curve. Made in R, using the rTPC package.

Therefore, this study asked: How does ocean acidification impact energetic expenditure across a range of ecologically relevant temperatures experienced by T. funebralis? To assess how ocean acidification and temperature interactively affect metabolic performance we conducted a mesocosm experiment to compare between two pH levels (ambient ~7.9; reduced ~7.7) across a gradient of eight ecologically relevant temperatures (12°C to 26°C, in 2°C increments). Respiration rates (O₂ consumption), a proxy for energetic expenditure through ATP production were measured after four weeks to generate thermal performance curves. Metabolic responses were then modeled using the Sharpe–Schoolfield equation, which incorporates enzyme kinetics to estimate key physiological parameters, including thermal optima and activation energy, under both ambient and acidified conditions. Results revealed a consistent pattern: sea snails exhibited significantly higher respiration rates near their thermal optimum (~22–24°C) under acidified conditions compared to ambient treatments, indicating that ocean acidification imposes additional metabolic costs even at temperatures typically associated with peak performance. This increase in oxygen demand likely reflects elevated energetic requirements for maintaining acid–base regulation and biomineralization under acidified seawater, where reduced carbonate ion availability (CO₃²⁻) constrains the chemical conditions necessary for shell formation. Together, these findings demonstrate that ocean acidification reshapes thermal performance by elevating metabolic demand, thereby constraining energy budgets and increasing the costs of maintaining essential physiological processes in a rapidly warming ocean.

Early Research Experiences

Bay Lab, UC Davis (2019-2021)

Population Genomics & Coral Adaptation

Conducted a collaborative global meta-analysis of reef-building coral (Acropora sp.) microsatellites to evaluate physical drivers of coral genetic diversity.

Advisor: Dr. Rachael Bay

Gold Lab, UC Davis BML (2019)

Molecular Paleontology & Geobiology

Investigated regeneration in moon jellyfish (Aurelia aurita) polyps under hypoxic conditions to explore cellular mechanisms of biological immortality.

Advisor: Dr. David Gold

Study Abroad, Guatemala (2017)

Wetland Ecology & Community Science

Analyzed the role of native versus invasive plant assemblage compositions on water quality parameters in wetland ecosystems in Lake Atitlán, Guatemala.

Advisor: Dr. Eliška Rejmánková