RESEARCH

Social Drivers of Environmental Change

“Science, in all its senses, is a social process that both causes and is caused by social organization. To do science is to be a social actor engaged, whether one likes it or not, in political activity. The denial of the interpenetration of the scientific and the social is itself a political act, giving support to social structures that hide behind scientific objectivity to perpetuate dependency, exploitation, racism, elitism, colonialism.”

Critical Ecology

Research Assistant (2024-2025)

Advisor: Dr. Suzanne Pierre

As a Research Assistant in the Critical Ecology Lab, I investigated how social power disparities that shape human activity also shape biogeochemical processes over time. Grounded in critical ecology, this research connected environmental patterns and processes to the societal structures that produce them, with the goal of empirically and mechanistically defining the social drivers of environmental change (e.g., economic inequality, structural racism).

One of the most well-known atmospheric hazards of the late 20th century is acid rain, largely driven by sulfur dioxide (SO₂) and nitrogen oxide (NOₓ) emissions released industrial activity. The Hubbard Brook Experimental Forest in New Hampshire became a landmark site for documenting the long-term biogeochemical consequences of these emissions. Decades of monitoring provided some of the first empirical evidence that acidic deposition from upwind pollution sources was altering soil chemistry and reshaping forest ecosystems. Research at Hubbard Brook helped establish the scientific link between distant emissions and local ecological degradation, informing the 1990 Clean Air Act Amendments and the Acid Rain Program. But while the research at Hubbard Brook clarified the where and what of acid rain formation, it left open the who and why? Who is most affected by the emissions that drive acid rain formation, and why are those facilities placed where they are? In collaboration with the Critical Ecology Lab and the Hubbard Brook Experimental Forest (HBEF), this project asked whether structural racism and classism help explain both the placement of major emitting facilities and the quantities of emissions that contribute to acid rain deposition.

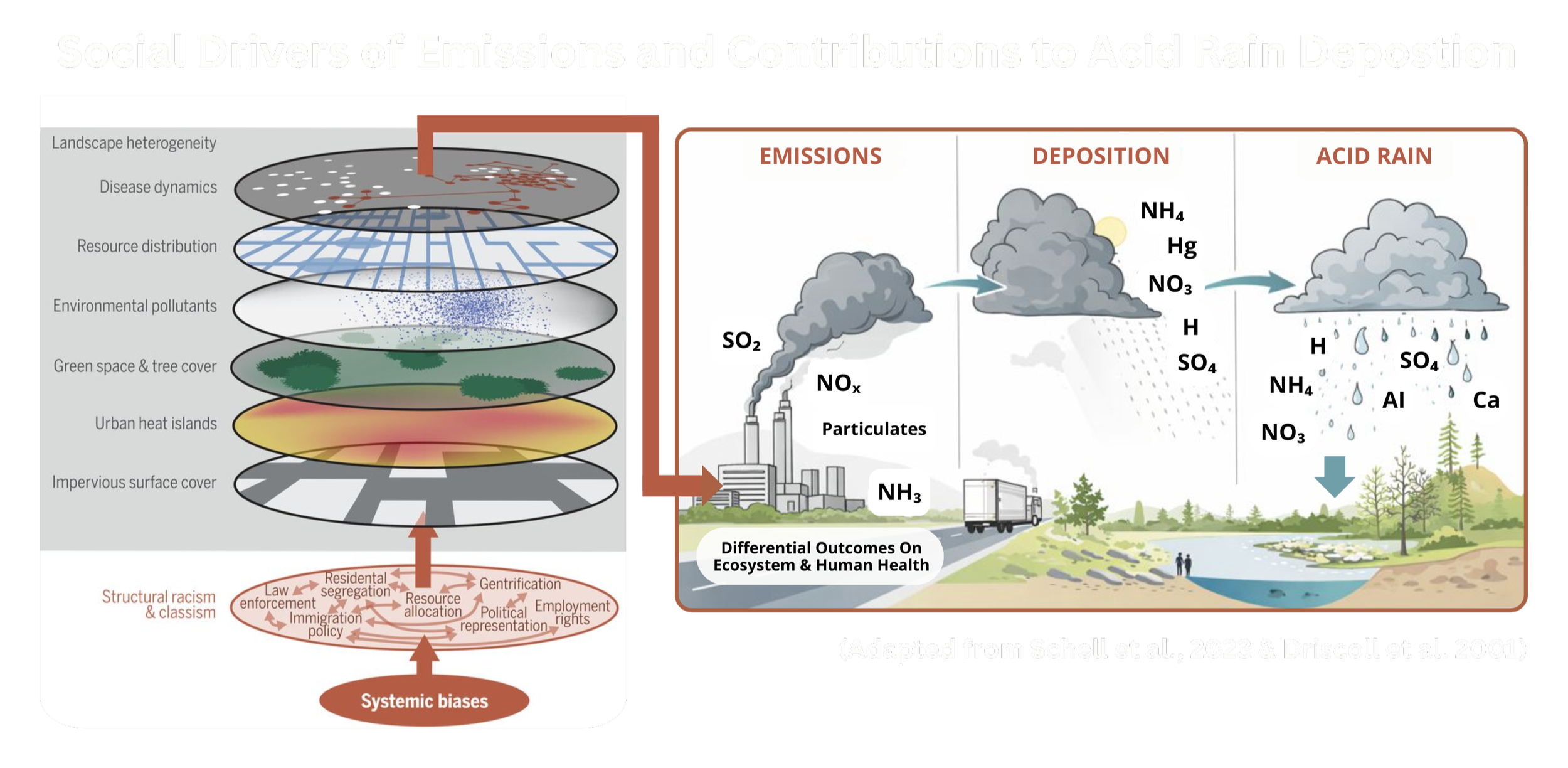

Figure: Conceptual model linking structural racism and classism to systemic biases that shape landscape conditions (e.g., green space, heat islands, pollutant exposure), and in turn influence pollutant emissions (SO₂, NOₓ, NH₃, particulates), atmospheric transport and deposition, and acid rain impacts. Together, these processes produce unequal outcomes for ecosystem and human health across places.

To answer this, facility locations and emissions of key states that contribute to acid rain at HBEF were mapped alongside two measures of inequality. The first measure was historical redlining, a federal-era practice that graded neighborhoods based largely on race and immigration status, shaping decades of investment and disinvestment. These maps, digitized by the Mapping Inequality Project, continue nearly a century later to predict where environmental hazards and harms concentrate, and where they do not, reflecting how segregation has shaped patterns of wealth and health across the United States. The second measure was present-day social vulnerability, which quantifies how demographic and socioeconomic factors (e.g., poverty, lack of access to transportation, and crowded housing) increase community risks across spatial scales and are mapped and maintained by the CDC through the Social Vulnerability Index. Using the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s National Emissions Inventory, this research compared how many major NOₓ and SO₂-emitting facilities were located across different redlining grades and vulnerability levels, and how much pollution each facility released on average.

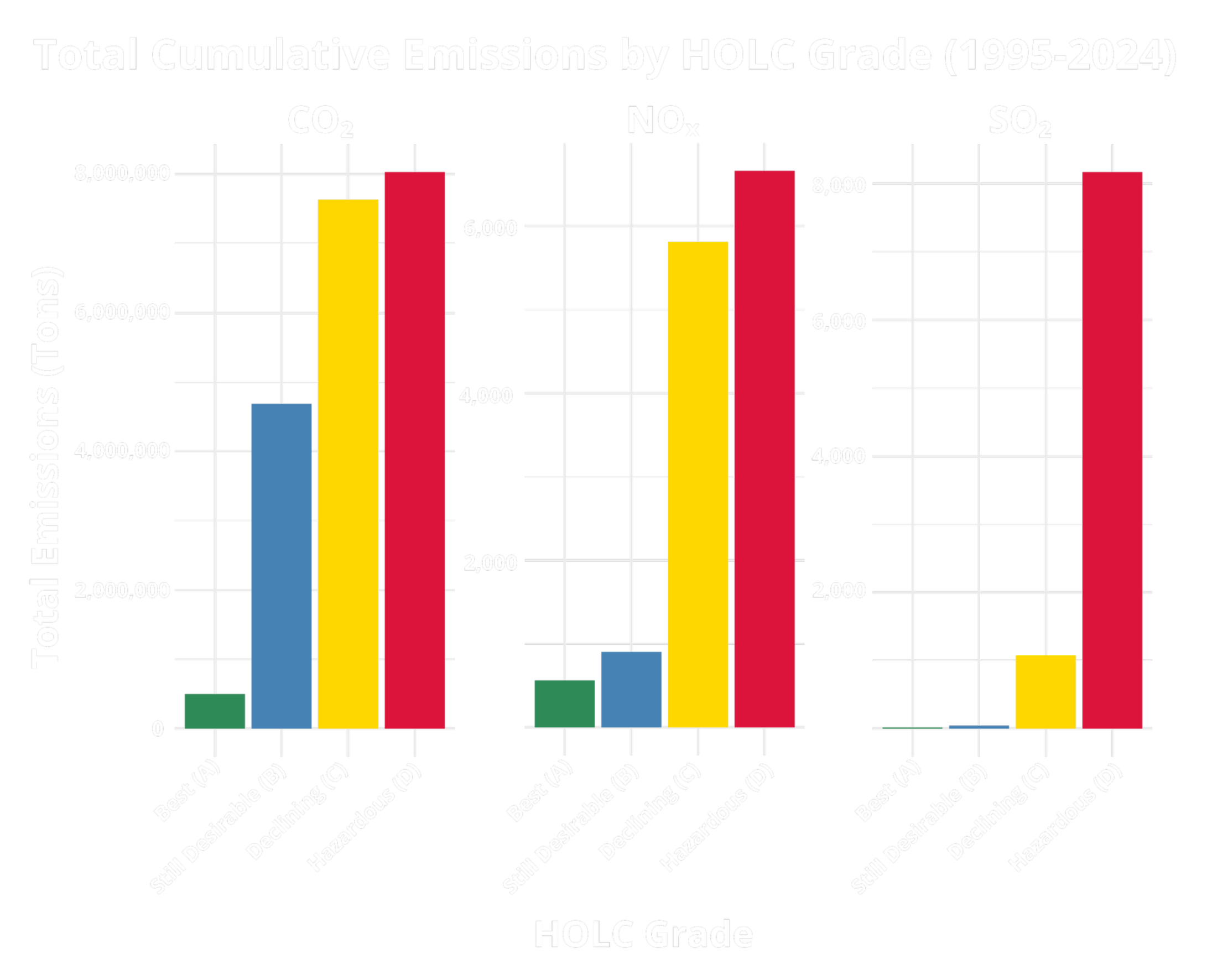

Figure: Total cumulative CO₂, NOₓ, and SO₂ emissions summed across facilities located within HOLC-graded neighborhoods, showing the highest cumulative emissions associated with areas historically graded C (“Declining”) and D (“Hazardous”).

Air pollution is not distributed randomly; its sources often reflect geographies of exclusion, shaped by race, class, and decades of policy and planning decisions. Results illustrated that neighborhoods that received the lowest historical grades (C and D), have significantly more major emitting facilities and showed higher average emissions per facility, and communities with higher social vulnerability were exposed to the greatest total emissions. In other words, the pollution linked to acid rain is not distributed randomly, it clusters in places shaped by segregation and vulnerability. These findings highlight how histories of land use and planning continue to structure environmental harm today, and why addressing inequality is not separate from remediating environmental harm. Reducing pollution at its source requires confronting the social systems that determine where emissions are concentrated in the first place; by linking spatial emissions data to indicators of inequality, this project contributes to broader efforts to understand how long-term environmental change is shaped by political and economic power.

Code and repository on GitHub [Link]

Policy-Driven Scientific Research

My experience at the science-policy interface centers on translating environmental research into actionable insights, especially in service of communities disproportionately burdened by environmental harm. Across federal agencies, private environmental firms, and interdisciplinary research programs, I have contributed to applied research that supports environmental regulation, restoration, and ecosystem-based management. As an Environmental Technician with Eco-Alpha Environmental Services, I conducted field-based water quality monitoring across municipal and industrial sites in California, sampling for contaminants in compliance with the Clean Water Act, while also supporting technical reporting and regulatory planning documents aligned with CEQA guidelines for the California State Water Resources Control Board. As an intern at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), I contributed to a Natural Resource Damage Assessment (NRDA) for a superfund site by conducting histopathological analyses of fish populations in an urban estuary to quantify ecological injury from industrial pollution, research that helped support legal accountability for corporate polluters and informed remediation strategies for ecosystem recovery. Most recently, as a fellow in the NSF Science- Policy Research Traineeship, I was trained to design "use-informed" science in active dialogue with coastal communities, resource managers, and policymakers; centering the co-production of knowledge to bridge environmental research with the social and political realities of environmental decision-making. By working across academic, governmental, and applied settings, my experiences enabled me to develop tools for communicating science beyond research spaces and strengthened a commitment to science that not only describes environmental change, but helps shape the decisions needed to repair harm, advance accountability, and safeguard ecosystem and community health.